A heartbeat, literally. That’s the time difference between number 1 and number 2 grid positions in the 2021 F1 Qatar Grand Prix during the Qualification Session number 3 in late November. Even more, the difference between the 2nd and the 3rd positions was just 0.1 seconds. But sure, this won’t be about F1, this is reflection of immediate and frequent feedback… and PDCA… and Kaizen…

Some background first. Pilots and Teams have 3 sessions to practice in the track on Friday and Saturday prior to start qualification sessions, which are usually 3. Thus, in a typical race, there will be 6 opportunities to fine tune the car, and the pilot, for the race on Sunday. The qualification sessions will decide the starting positions for the Sunday race. And the better you start, the higher probabilities of winning the event!

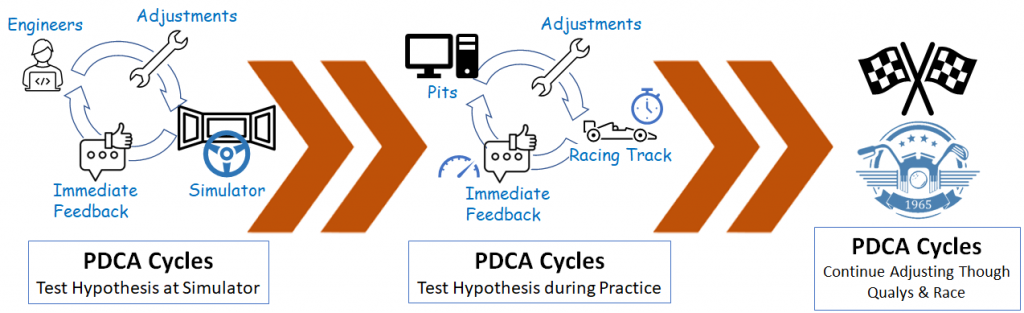

Practice sessions come after hours of work in a simulator, where pilots practice and test the changes made to the car in preparation for that specific racing track (there are 22 in this year’s championship). Using Kaizen terminology: they simulate the changes and test their hypothesis before making changes to the car, or the driving style.

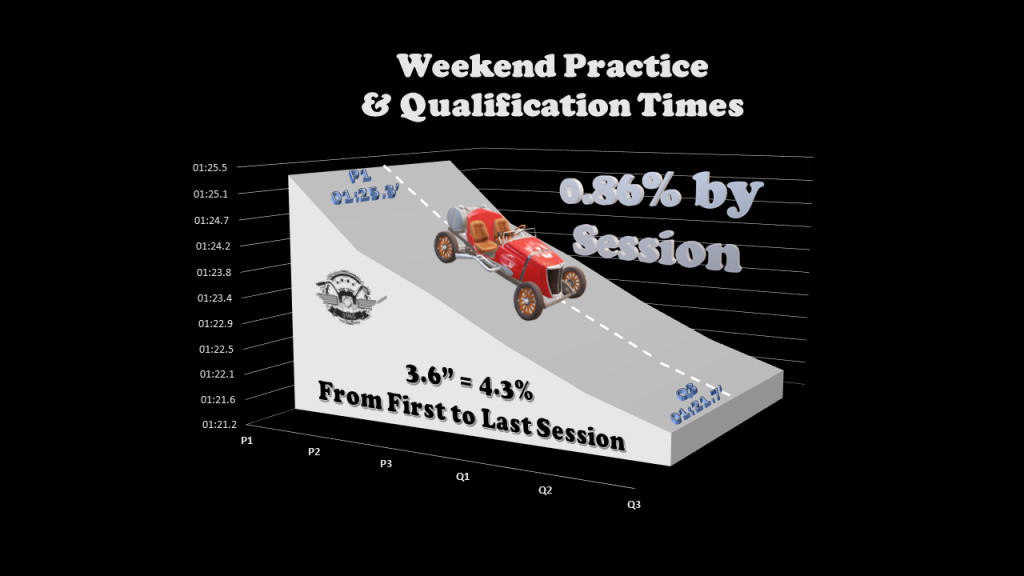

Once in the practice sessions, on the racing track, which typically consists of somewhere between 15 to 25 laps each, they adjust physical characteristics of the vehicle chassis and engine, they test software limits and practice driving styles. They also prepare the strategy for the real race on Sunday. The result? If we average all drivers’ (20 of them) fastest laps during the 6 sessions (Practice and Qualys), there is a 3.6” reduction, which equals 4.9%, from the first practice to the last qualification run. If you think this is not much, please refer to the difference in time stated in the title of this article…

The average session-over-session improvement is 0.86%. That represents small increment improvements which accumulated over time make a big difference in the result. This is what some would call Kaizen, isn’t it? Let me look at it from other continuous improvement angles.

Each lap in a practice session is an opportunity to Check what was Planned in terms of car and driving changes. An Adjustment will come soon. A beautiful PDCA cycle! But not only that, the feedback is happening in real-time. The Race Engineer, Performance Engineer and the Pilot are communicating, analyzing and adjusting in real time. They don’t wait for another race, not even for tomorrow. They make modifications between sessions or even stop at the pits and then resume the testing (Sop and fix, somebody would suggest…).

This immediate feedback and adjustment are not exclusive to the Formula 1 races in the sports world. You could argue that fighters and boxers have the quickest feedback of all! You adjust at the line of scrimmage and at every pitch in baseball. You change your game strategy at half time in a soccer game…

At work, feedback comes in different ways and at different pace, but it always does. And then we can adjust, completing the PDCA cycle. Again, and again. Don’t we?

As a matter of fact, most organizations give a specific time in the year for supervisors to provide feedback to employees so they can adjust and improve. Sometimes twice per year. That is immediate feedback, right? Mmmmh, maybe not. But nothing prevents supervisors and managers, customer and peers, to give more frequent, timely feedback so we can adjust and learn or continue doing what we are doing well. Organizations promote frequent feedback.

But let’s continue our analogy by not looking at the leader’s feedback, but to the other crucial point in adjusting for the F1 race: testing hypothesis at the simulator or the track before making final changes. Kaizen practitioners will tell you that is a key principle during Kaizen events:

- You observe and analyze the situation or problem (a gap to the desired or ideal state)

- Discuss potential solutions and pick one

- A hypothesis is generated: the solution to your problem

- The hypothesis is tested: a simulation is held at Gemba without making real changes to accept or reject the hypothesis. This should be cheap and fast

- After several cycles, if needed, the solution is implemented, and the cycle can begin again

If this works so well in continuous improvement events, why can’t it work on other day-to-day environments or activities?

- As leaders or organizations, do we give opportunities to test hypothesis and learn? Or do we direct our employees in how to do things every time?

- Do we promote it experimentation and learning? When we do, does it include feedback on the results and performance?

- Do we acknowledge that failures will get give learning and eventually move us to success?

“Really, you should always discuss the defeats because you can learn much more from failure than from success.” – Niki Lauda

I don’t think I will ever drive a car that fast! But I can continue enjoying the thrill of watching a driver winning the pole position by a tenth of a second: less than a heartbeat, or a blink of an eye! And I can continue testing hypothesis and adjusting from feedback, implementing Kaizen and learning from mistakes. Not on the race track, but in other aspects of work and life…